By: Brian Ball, Alex Cline, David Freeborn, Alice Helliwell, and Kevin Loi-Heng

With support from the Ethics Institute, the Internet Democracy Initiative, and the NULab for Digital Humanities and Computational Social Science, all at Northeastern University.

Introduction

What do we know about the publication landscape for research and scholarship on AI ethics? How are the individual authors, journals, and publishers related to one another in this interdisciplinary ecosystem, and what topics do they discuss? In this post, we undertake a preliminary network analysis of a moderately large corpus of academic papers in the field, and report some initial findings.

As the present project involves the techniques of the digital humanities, we begin by describing our dataset – a collection of several thousand documents available on JSTOR. We then give some preliminary (e.g. temporal and statistical) analysis of our data, before exploring a series of networks – of authors, publishers, and keywords – made visible within it. The result, we hope, gives an initial impression of the AI ethics research community over the years.

The Dataset

Our dataset comprises metadata from some 7076 documents from JSTOR, all wholly or partly in English, found with the search ‘artificial intelligence AND ethics’ through the (now defunct) Constellate platform.[1]It is, of course, far from obvious that this search provides the most appropriate method for selecting documents from the JSTOR repository: for the category of AI ethics may not be (purely) conjunctive; ‘AI’ may modify ‘ethics’ in the phrase ‘AI ethics’ in something like the way that ‘giant’ modifies ‘shrimp’ in the phrase ‘giant shrimp’.[2]Thus, in particular, it is possible that our search is too inclusive: a paper that is about the use of AI in medicine, for example, may also have some material on (e.g. research) ethics, without being clearly about the ethics of AI use in medicine; or an ethics overview paper might mention AI, and yet not be an AI ethics paper properly so-called. Still, we feel it is better for our corpus to be too encompassing at this stage, rather than too narrow – and a search using ‘AND’ is clearly more appropriate than one using ‘OR’!

It is also worth noting that our corpus is neither unrepresentatively small[3](like, say, a case study of the 100 or so papers taught across a course or two on the topic[4]), nor unwieldy and huge (such as all of the papers in e.g. ArXiv might be). Thus, while it is perhaps not exhaustively indicative of the AI ethics literature as a whole, we do hope to be able to learn some interesting things about the research community and publishing landscape for AI ethics by examining it.

Preliminary Analysis

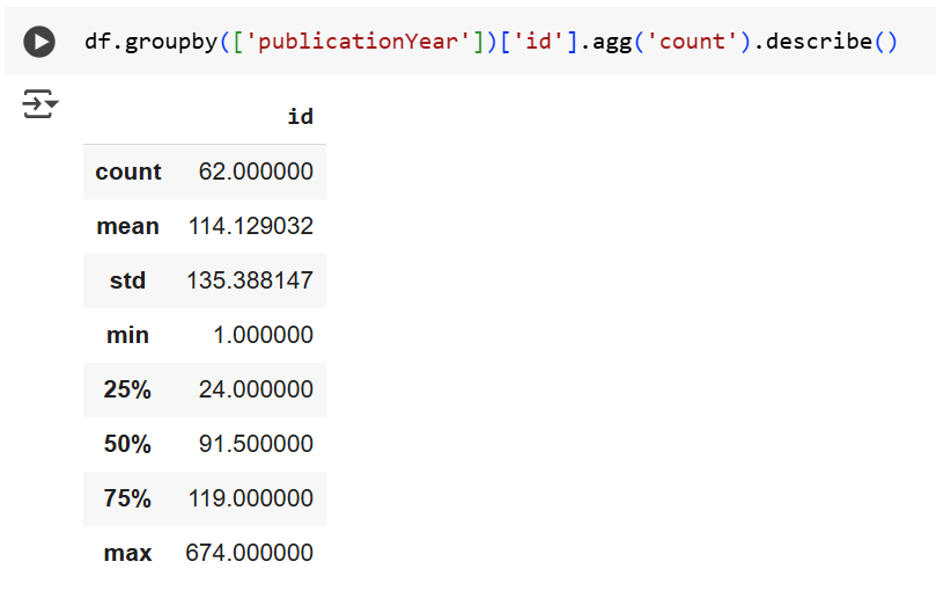

We did not explicitly restrict attention to recent years in choosing our dataset – and yet 1961 is the earliest recorded publication year in our corpus. Moreover, amongst years with at least one publication, there were an average of 114 publications per year, with a minimum of 1, a maximum of 674, and a standard deviation of 135. There were fewer than 24 papers in a quarter of years, at least 91 papers in half the years, and 119 or more in a quarter of years. This said, some years had no publications – which obviously affects these statistics.

There is a spike in publications 1988, with 152 documents – a number that is not passed until 2016.[5]There was an increase in the number of documents from 2016 (194 docs) to 2020 (674). The fact that there are fewer papers after that (in the years 2021-2024) no doubt reflects JSTOR’s archiving (and copyright agreements) rather than a drop off in interest in AI ethics within the community – and there are still more than 300 per year in those most recent years.

The literature we are examining is varied in format. Document types in our dataset include: ‘book’ (578 items); ‘research_report’ (827 items); ‘article’ (5045 items); ‘chapter’ (514 items); ‘document’ (103 items); and ‘newspaper’ (9). Of these, 341 documents have the title ‘Front Matter’. A further 61 are called either ‘Review’ (2) or ‘Review Article’ (59). This seems to us to be a fairly representative collection of research texts.[6]

There are some 596 unique ‘publishers’. Of these 25% have published just one document, 50% have published 3 or fewer, and 75% have published 9 or fewer. Only 9 publishers have published more than 100 documents: together they account for 1780 documents (just over 25%). The top 25 have published 60 or more documents.

There are 1395 unique journals – or at least, items of which documents are parts. (The metadata field under discussion is called ‘isPartOf’ – of course, this comprises books of which chapters are parts, as well as journals, and perhaps other items as well.) Of these 25% contain just one document from the dataset, 50% contain 2 or fewer, and 75% contain 3 or fewer. The top 100 contain 11 or more documents. The top 50 contain 21 or more. 12 contain 50 or more. 3 contain 100 or more.Synthesetops the list with 230 articles in our dataset.

5265 of the documents have something in the ‘creator’ (i.e. author) field. (This field is blank in the remaining items in our corpus.) But some of these contain multiple authors (that is, they are co-authored documents). Our dataset contains some 9297 unique authors/creators. Only 32 of these have authored 10 or more documents in the collection, however.[7]For the sake of anonymity, we will not comment in detail on authorship in what follows – though we will use the ‘creator’ field to build networks representing the publication landscape (see below).

Of our 7076 documents, all but 60 include ‘keyphrases’: and indeed, our dataset contains 30,836 unique keywords/phrases. On average a keyphrase occurs in two and a quarter documents. Over 75% of keyphrases occur in just a single document. Again, we will explore these keyphrases in our network analysis below – but it is worth noting some basic descriptive facts first. The most used keyphrase occurs in 667 documents: it is the word ‘philosophy’. The phrase ‘artificial intelligence’ is the third most frequently occurring keyphrase, with 567 occurrences. There are 5 keyphrases that occur in at least 500 documents: philosophy (667), university (582), artificial intelligence (567), science (539), technology (509). Some 39 occur in at least 100 documents, 12 in 200 or more, and 98 occur in 49 or more.

Networks

The above analysis is of interest: it tells us about the various individuals and other entities that have a presence in the AI ethics literature (as represented in our dataset); but it does not say much, if anything, about the relationships between those entities (as captured by the JSTOR metadata at our disposal). In what follows we conduct some network-oriented analysis in an attempt to reveal the publishing landscape and research ecosystem in AI ethics (in our data).

It is fairly common, when constructing academic publishing networks, to focus on either co-authorship (of documents) or citation (of one document by another) to establish links between individuals (authors) and/or entities (documents). But joint authorship is not that common within fields like philosophy (which, recall, was the most common keyword in our corpus); and that sociological fact is reflected in our data, where more than three quarters of the documents list a single ‘creator’. Accordingly, any co-authorship networks we might construct would be highly disconnected, revealing very little structure within the AI ethics research community. Citation networks might be more illuminating: but our JSTOR corpus metadata does not include information about citations; and so, producing such network representations about our corpus would require (a) investigating a different dataset (the full texts of the papers in question), and (b) using radically different computational techniques (e.g. named entity recognition). This is not something that we will undertake here.

What our (meta)data does (directly) contain is information that links documents to their creators, the journals (or books) they were published in, the publishers of those (books or) journals, the keywords used to describe them, etc.; and this information can in turn be used to induce relations between those items (as mediated by the documents).

Author Networks

For example, here is an image (produced using Gephi) of the (unlabelled) authors represented in our dataset, as linked by the existence of a journal, book, or other collection, containing as parts documents written by each. (This will include cases in which it is the same document that is co-authored by the two parties in question.) Darker nodes (and edges emanating from them) indicate authors with greater ‘betweenness centrality’ – that is, they are authors who lie on more of the shortest paths between other authors (which in the present context means that, if one wishes to progress from a document written by one of those authors to a document written by another, via works containing documents with authors in common, one is likely to progress via works by these darkened authors).

In the next image, by contrast, we see the same network (of authors connected by shared journals/collections), but with darker colour indicating higher degree. That is to say, here the darker nodes are those who are connected to more authors (by being included in the same publication): they are, in some sense, the most connected members of the community; but their connections may not be the most essential ones within the community (as the connections of the betweenness central nodes are).

Publisher Networks

Next, we see a (labelled) network of the publishers in our dataset, linked by the existence of (one or more) authors who have had works published by both. Here we can see that the network is disconnected, meaning that some collections of publishers share no authors with other collections of publishers. In some sense, then, the AI ethics research ecosystem (of the past 60+ years, as represented in JSTOR data) comprises several distinct subcommunities. Colour here indicates modularity – another sort of (algorithmically detected) sub-community, though as can be readily seen, not one that is so discrete. (Indeed, the algorithm is stochastic, and sometimes yields different module assignments if run on the same network.) As can also be seen, Springer is (in some sense) the most influential publisher of AI ethics research.

Keyword Networks

Finally, in the image below, we can see a network comprising the 13k+ keywords used in the metadata for our corpus of papers, linked by (one or more) authors who use it to describe their work. Obviously labels are not visible for all of these keywords – but the larger words are readily discernible, with size indicating eigenvector centrality (roughly, being more linked to other keywords that are themselves also more heavily linked). One thing that emerges immediately is that ‘artificial intelligence’ is the most prominent keyword in this network – even though ‘philosophy’ is more commonly used, as we saw above. This tells us that ‘artificial intelligence’ is used in our dataset by authors who also use other widely used keywords; whereas ‘philosophy’ is perhaps slightly more likely to be used alongside words that are somewhat more idiosyncratic? Or perhaps this just tells us that the field of AI ethics is interdisciplinary – so that all authors in the field are likely to use this word alongside others, whereas only a subset of them are likely to use ‘philosophy’ in conjunction with whatever else they are discussing.

Conclusion

Clearly, we have only begun to explore this dataset of documents from the AI ethics literature available on JSTOR – there remains plenty of more in depth analysis to be done with this collection of thousands of publications totalling over 150m words – but already we can see how the decision to represent the research ecosystem in this area using network techniques can prove illuminating. Communities of researchers are held together by relational ties – e.g. to publications and publishers, and thematically by keywords – and through graphical representation we can begin to (literally) see the shapes these communities take. This in turn can guide further investigations, suggesting questions for exploration – which we look forward to pursuing in due course!

[1]See here:https://labs.jstor.org/projects/text-mining/. Constellate is also on GitHub – see e.g.https://github.com/ithaka/constellate-notebooks/blob/master/Exploring-metadata/exploring-metadata.ipynb

[2]Though hopefully not in the way ‘counterfeit’ modifies ‘money’. Counterfeit money is not really money – but with any luck, AI ethics papersareethics papers!

[3]Indeed, the total word count in our corpus is159,077,064 words (i.e. 159m+ words)!

[4]See e.g.https://cssh.northeastern.edu/nulab/analysing-ai-ethics-using-ai/.

[5]Perhaps it is better to say that there is a fall in AI ethics publicationsafter1988 (until the late 2010s). This corresponds roughly to the so-called (second) AI winter, which was characterised by decreased optimism around the prospects for AI technology, and cuts in funding to AI-related research in the USA, Japan and elsewhere.By way of (admittedly rough) corroboration, the pattern for “artificial intelligence” in Google Ngram is very similar – seehere. In short, the decline in publications in the late 1980s seems to be primarily in AI, not ethics.

[6]This said, our metadata on the documents includes a ‘docSubType’ field. Here we find the following: book (578); research report (162); chapter (524); research article (2944); mp research report (286); miscellaneous (1805); index (47); book review (297); references (109); introduction (63); front matter (122); table of contents (9); notes (48); appendix (17); back matter (24); correction (4); other (11); review article (1); preface (4); glossary (1); forward (0); review essay (8); and news (9). So there are perhaps a few more reviews, short pieces, and other (what we might call) ‘atypical’ documents in our corpus than the above ‘docType’ analysis suggests – but not so as to seriously affect our findings.

[7]The World Health Organization (WHO), for example, is the second most common ‘creator’, with 41 distinct documents.